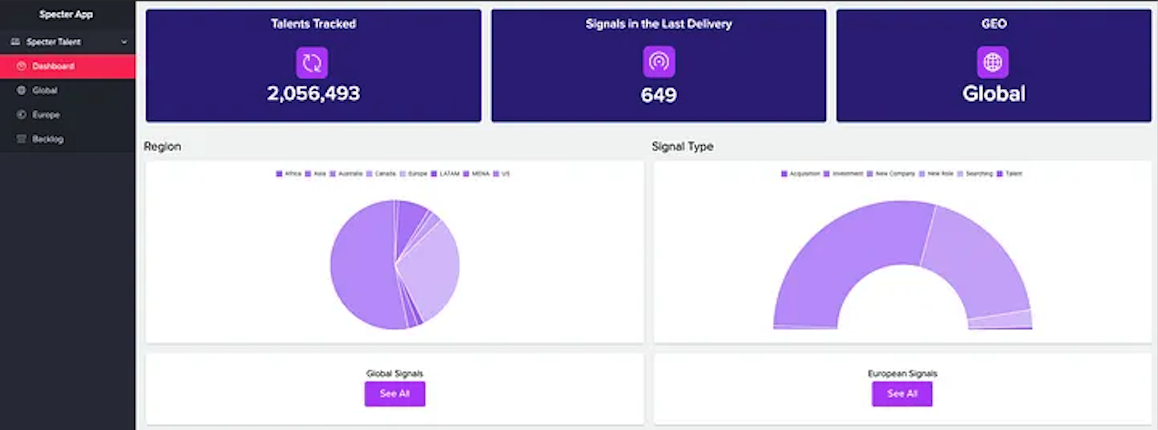

Specter Talent

1. The Core Problem in Venture Discovery.

My journey with Specter began as an intern, joining a small team trying to solve one question that always frustrated investors: why do funds learn about promising founders so late?

By the time a company officially surfaces through a funding announcement, a landing page, or a Product Hunt launch, most serious conversations have already happened behind the scenes. Investors needed a way to understand entrepreneurial intent before any “public company signal” existed.

That problem became the foundation of Specter Talent. The product was built on the belief that early signals hide in plain sight, and if we could learn how to capture them, we could give investors a view of the future before it became obvious. Over the next five years, I went from supporting its early experiments to building its signal logic, leading the product, and helping shape how Talent detects founders long before anyone else knows they’re building.

2. First Hypothesis: New Companies as the Primary Signal.

In the earliest phase, we tried to detect “New Companies.” We thought that new entities forming online would always be the first and most relevant signal. We scraped incorporations, domain registrations, fresh landing pages, half-formed product listings, and tiny web footprints.

The premise seemed reasonable, but repeated failures showed us the opposite. Many company entries were experimental or never went anywhere. More importantly, we kept finding cases where the founder’s decision to build began much earlier than the company’s public trace.

If the company signal was arriving late, then we had to look further upstream.

3. Breakthrough Insight: Founders Always Surface Before Companies.

While reviewing thousands of raw signals manually, one pattern repeated consistently: people reveal intent much earlier than companies do.

They update LinkedIn bios to “Stealth,” begin GitHub repos aligned with problem spaces, join accelerators before launching publicly, add themselves to founder databases, or leave subtle breadcrumbs after exiting previous roles.

The strongest signal we found: a person leaving a role and adding a stealth marker soon after. That behavior correlated tightly with genuine intent to build.

This gave us the direction for Talent: a founder-first discovery layer.

4. Evolving the North Star Metric: Weekly New Founders Discovered

Once we realized the earliest signals exist at the founder level, we changed how we measured success. Initially, we tracked new companies surfaced per week — but that signal was too late and too noisy.

The new North Star became: weekly new founders discovered.

This matched the natural rhythm of strong signals and provided room for verification, enrichment, and context-building. It also forced discipline: fewer false positives, more relevant detections, and deeper founder profiles.

5. My Role and Journey: From Intern to Investment Analyst to Leading Talent.

I joined Specter after cold-mailing Marco, the co-founder, and became deeply embedded in building Talent’s intelligence. The work was intensely hands-on — scraping sources, parsing unstructured text, reconciling names, rejecting weak signals, validating hypotheses, and debating logic with engineers across multiple countries.

I learned indirectly from VC users through demo call summaries, feedback threads, and forwarded conversations. Over time, patterns emerged around which metadata they valued most — background, previous experience, education, location, sector, or technical ability. Each repeated request eventually became part of Talent’s enrichment logic.

As the system matured, I moved into an Investment Analyst role and eventually led Talent. That meant refining signal logic, managing enrichment cycles, curating weekly discoveries, fixing broken scrapes, and continuously evolving the product as founder behavior changed.

6. Early Delivery: From CSV Files to Zoho Creator.

Talent began as weekly CSV exports. These simple files validated that founder-first discovery resonated with investors — even without UI.

But CSVs stripped context and made meaningful signals feel flat. Our first UI was built on Zoho Creator — functional, but too limited to express the depth of Talent’s intelligence.

This disconnect eventually pushed us to build a dedicated interface that could represent signal strength, founder context, sequences of events, and the entire footprint of early intent.

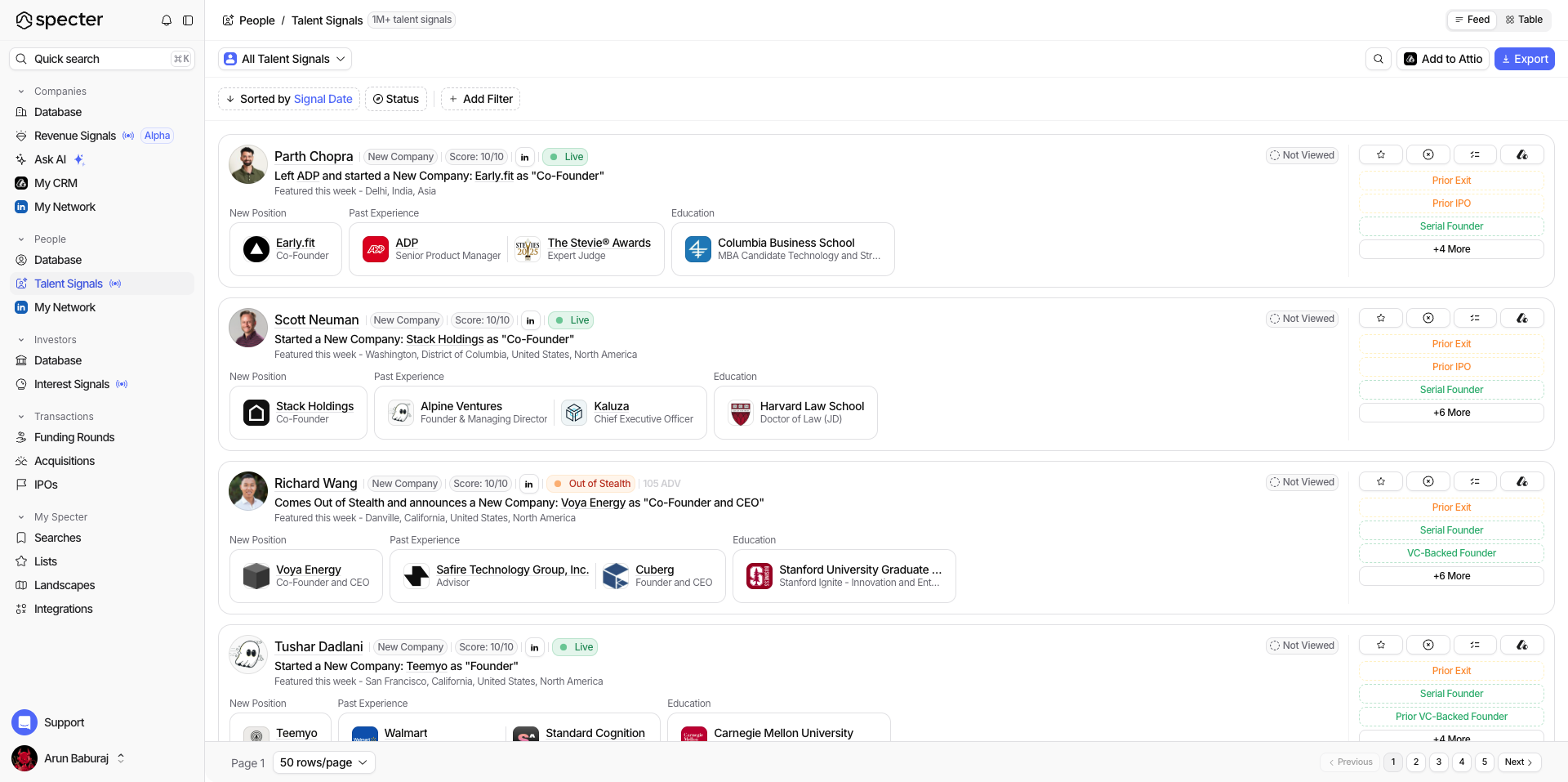

7. Signal Design and the Birth of the Signal Score.

Not all signals are equal. A domain registration with no surrounding activity means little. A stealth keyword added immediately after leaving a role means much more.

Through thousands of samples, we learned how timing, context, and event sequencing correlate with genuine founder intent.

This evolved into the Signal Score — a quantitative measure that ranks founder credibility based on strength, timing, and cross-source validation. It made Talent more discerning and reduced noise dramatically.

8. Understanding User Needs Through Second-Degree Conversations.

I didn’t speak directly to VC users, but I learned from what filtered back through the team: repeated requests for metadata fields, questions about missing context, confusion around certain attributes.

These second-degree insights shaped Talent’s information architecture more than anything else. Location, education, experience, contextual notes — all emerged from recurring friction points.

9. A Weekly Feed of Founder Discovery.

One of Talent’s most powerful surfaces was the weekly founder feed. It showed emerging markets before they existed.

Some weeks saw clusters around automation, others around AI, climate, or fintech. Seeing founders before companies helped analysts anticipate where innovation energy was moving.

10. Talent as a Revenue Driver: The Product That Carried Specter.

Today, Talent contributes roughly 60% of Specter’s revenue. It stands out because it delivers what most platforms cannot: visibility into people before they become companies.

From a CSV experiment to a core business engine, Talent proved that founder intelligence is commercially essential.

11. The Front-End Evolution: Reflecting the Intelligence We Built.

Building a dedicated interface changed everything. Profiles gained structure, signals gained clarity, and stories became traceable.

The UI finally reflected the intelligence we had been building for years — helping analysts interpret early intent as a coherent narrative rather than scattered breadcrumbs.

12. What Building Talent Taught Me.

Five years of working on Talent taught me how noisy, ambiguous, and unstructured early-stage markets really are — and how much clarity emerges when you study the noise long enough.

I learned to read digital exhaust as direction, distinguish weak fingerprints from strong intent, and identify founders long before their companies appear.

It reshaped how I think about products, data, and venture ecosystems.

13. Closing Reflection.

Specter Talent began as a question about companies, but became a study of the people behind them. Entrepreneurial intent leaks early — if you know how to look for it.

I’m grateful I got to help build a system that detects these individuals at their earliest moments. Those years shaped how I think about venture, innovation, and discovery.

If you want to see what’s coming next, you follow the builders first.