HomeHunter: A Rental Marketplace I Chose Not to Scale

HomeHunter was built with the intention of simplifying rental accommodation discovery for Gen Z and Millennial renters.

The idea came from a very personal place. Whenever friends or family members planned to move to Bangalore, my friends and I often became their first point of contact.

We would be asked to help find a place that matched their preferences, budget, and timelines.

Despite the presence of well-known platforms like NoBroker, MagicBricks, and 99acres, this process was consistently painful.

After visiting multiple properties across different localities, I started noticing recurring patterns in how rental discovery actually worked on the ground.

Some of the most common and frustrating issues were unspoken but widely enforced.

House owners or brokers often preferred vegetarians over non-vegetarians (at least in old Bangalore).

There were strong preferences around religion or community. Families were favored over bachelors or single tenants.

Brokers frequently reused the same listings across multiple platforms. Many rules felt outdated and arbitrary, yet they directly influenced outcomes.

These constraints were rarely visible upfront. Renters would spend days shortlisting properties, visiting homes, and following up, only to be rejected at the very end because they did not fit an unstated criterion.

The cost was not just time, but emotional fatigue.

Initial hypothesis

My core hypothesis was that rental discovery in India fails early because critical decision-making constraints are hidden.

In a country with frequent intercity migration and diverse cultural backgrounds, supply-side preferences play an outsized role in who gets access to housing.

House owners often rely on heuristics shaped by past experiences, community familiarity, and perceived risk.

These preferences, whether around marital status, food habits, or religion, act as invisible filters.

Renters only discover them after investing significant effort.

I believed that if these constraints could be surfaced during the discovery phase, many wasted cycles could be eliminated.

A bachelor moving cities for a new job should not have to visit multiple properties only to be rejected later for being a bachelor.

If those preferences were visible earlier, discovery could become more efficient and less frustrating.

The bet was that better information, not more listings, was the real unlock.

What I built and why

I started building HomeHunter in Bengaluru and later extended it to Chennai, Delhi, and Hyderabad.

Since rental discovery is a marketplace problem, I focused first on solving the cold start challenge.

I chose to start with supply aggregation, which I believed was the harder side of the network.

At the time, a large volume of real rental inventory lived on Facebook groups and Twitter threads, especially in groups like Flats and Flatmates.

I joined every relevant group I could find and actively searched for keywords on Twitter.

By manually collecting posts every morning and evening, I was able to source roughly fifty new listings per day.

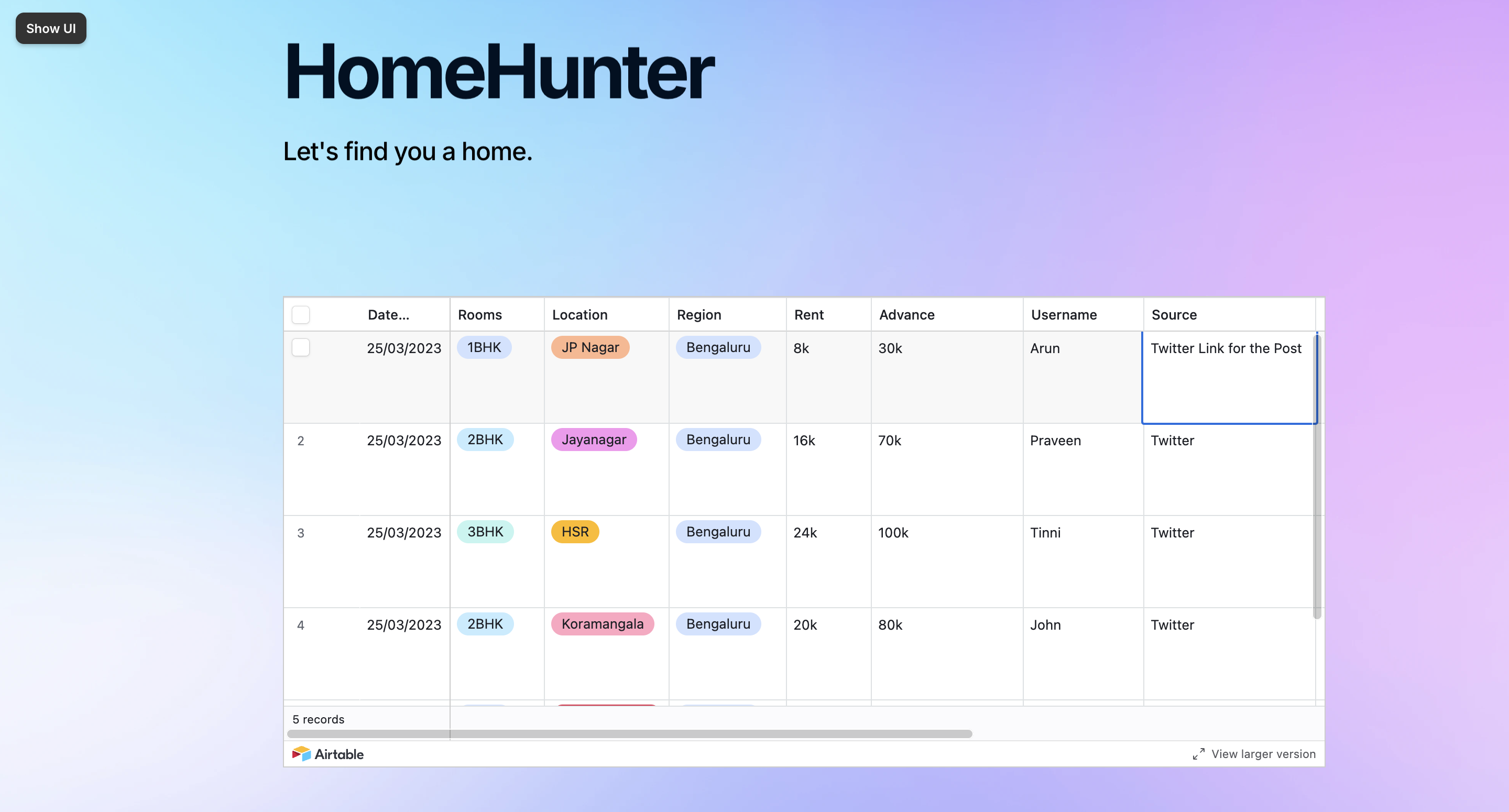

The first version of the product was intentionally simple. I used Airtable as a database to store listings and shared a filtered view on the website.

The goal was not polish but speed. I wanted to test whether aggregated, hard-to-find listings had real demand.

To acquire users, I commented on rental queries across social platforms and openly shared the HomeHunter link.

This drove a steady inflow of users who were seeing listings that were not easily accessible through traditional platforms.

Early traction and scaling attempts

The first two weeks showed strong early signals. The site received close to one thousand daily visitors.

As manual data collection became time-consuming, I looked for ways to scale sourcing.

I began using PhantomBuster to scrape Facebook groups and then manually cleaned and structured the data before adding it to Airtable.

This reduced the time spent on sourcing and improved consistency.

By the fourth week, daily traffic grew to around two thousand users. Discovery demand was clearly present.

However, this momentum was fragile. PhantomBuster discontinued Facebook group scraping after Facebook updated its terms.

I attempted a short-term workaround by building a custom Python scraper, which worked briefly but eventually led to my account being restricted for violating platform policies.

At that point, returning to manual sourcing was no longer viable.

More importantly, the incident forced me to confront a deeper issue.

What users actually did

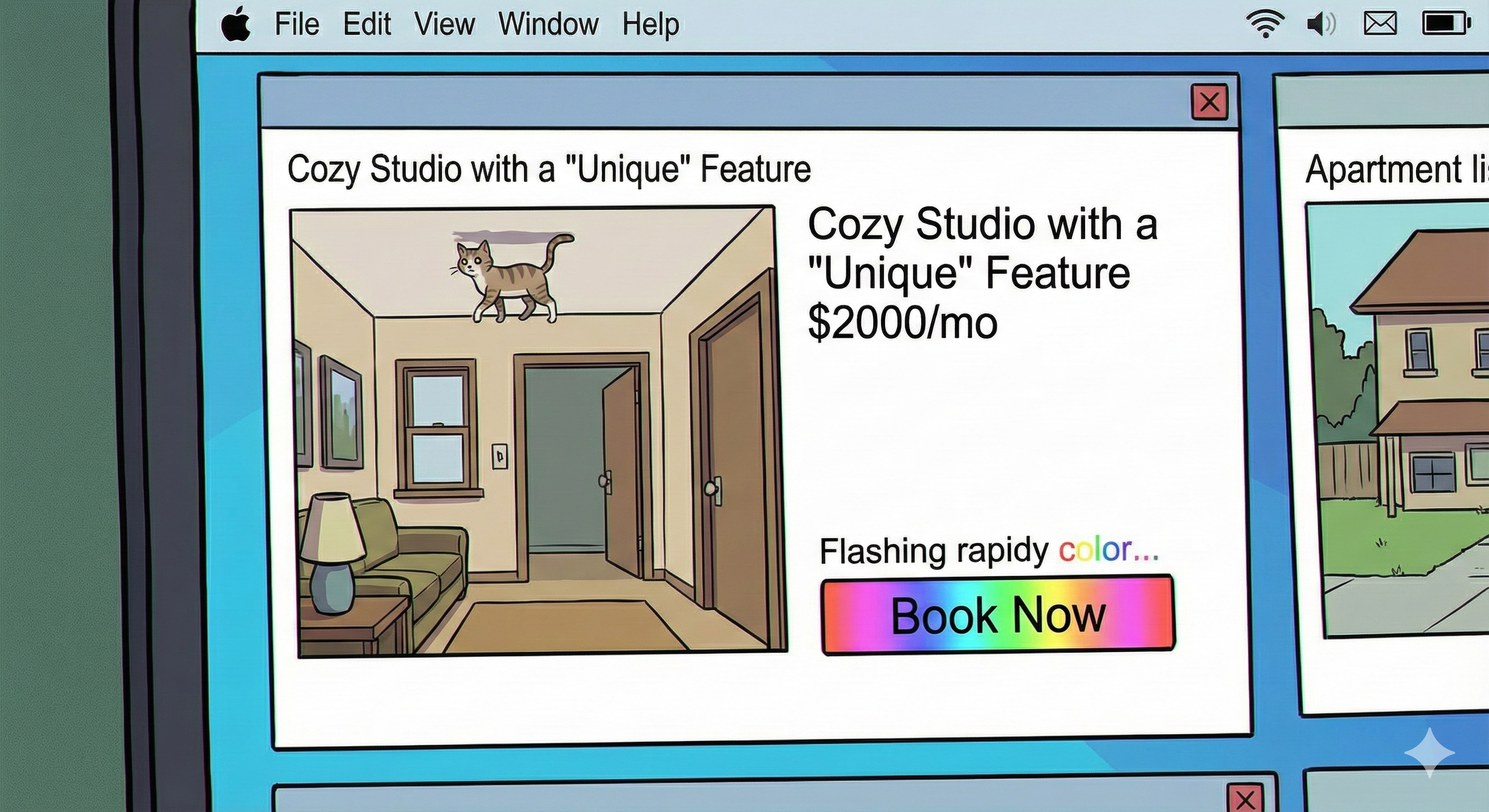

While HomeHunter performed well as a discovery layer, it consistently broke down at the point of contact.

Many source posts did not include direct contact details. Users had to click through to the original Facebook or Twitter post to reach the owner.

If the post lived inside a private group or a restricted account, users were forced to request access.

This broke the flow entirely. Users liked listings but could not act on them immediately.

Churn concentrated heavily among users who could not reach property owners through the platform.

Their journey often ended the moment they encountered a closed group or missing contact information.

In practice, the product was only as good as the completeness and accessibility of third-party data.

The real core flaw

I initially tried to solve the marketplace cold start problem by fixing the supply side through aggregation.

This worked in the short term, but it relied on several high-risk assumptions.

The supply was borrowed, not owned. Any advantage could be revoked without notice.

The data required to validate my core hypothesis were inconsistently available across posts. This made differentiation difficult.

Even with growing traffic, defensibility remained weak.

The deeper flaw was that HomeHunter depended on temporary access to someone else’s network rather than creating a durable incentive for house owners to participate directly.

Even if the platform had reached escape velocity, success would still have depended on convincing owners to change entrenched listing behavior.

That shift required trust, incentives, and offline validation that software alone could not provide.

Why I chose not to pivot

When the supply pipeline broke, I evaluated whether the product could be meaningfully pivoted instead of shut down.

The obvious options involved actively onboarding house owners, partnering with brokers, or running a more operations-heavy model to verify and manage listings.

Each of these paths required solving trust and coordination problems through manual effort rather than product leverage.

None of them removed the core risk or improved defensibility. They only shifted complexity into operations.

Given the lack of a clear, scalable path that aligned with the original thesis, I decided that continuing would be a poor use of time and effort and chose to sunset the project.

How this changed my product thinking

Working on HomeHunter fundamentally changed how I evaluate product ideas, especially marketplaces.

I now place far greater emphasis on supply-side incentives and defensibility before investing in demand-side experience or growth.

Early traction taught me that usage alone is a weak signal when the underlying behavior change is fragile.

I have also become more cautious about products that rely on borrowed platforms or policies outside my control.

Most importantly, this experience helped me better distinguish problems that software can realistically solve from those that require sustained operational effort.

Since then, I have been more disciplined about validating leverage, incentives, and long-term risk early rather than optimizing for short-term momentum.